Determining ARM firmware base addresses

A common problem when reversing a firmware blob is to determine the correct offset at which to place the firmware file in memory. Recently, while doing some research into possible solutions, I came across a paper by Zhu et al. The paper proposes an approach that exploits the addresses found in 32bit ARM literal pools to determine the correct firmware offset. I was able to successfully implement and use their approach to determine the offset of two firmware blobs. In this post, I present my implementation: First, I give a quick overview of ARM literal pools. I explain the algorithm concept and provide a detailed analysis of my implementation.

ARM Literal Pools

Instructions in 32bit ARM can have a length of two or four bytes. This design choice poses some restrictions on how an address can be loaded into a register since a full 32bit address is too long to fit into a single instruction. The following code snippet provides an example of such a scenario:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

char foo(char *arr) {

return arr[0];

}

int _start() {

char a = foo("Bar Baz Buzz\n");

char b = foo("Bar Baz Buzz 22\n");

return a & b;

}

In order to call function foo, the compiler must place the address to the string literals in register r0. Since the strings are stored in the .rodata section of the application, they are potentially located out of range for PC-relative addressing. Hence, the compiler generates the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

00008028 <_start>:

...

8034: e59f0038 ldr r0, [pc, #56] ; 8074 <_start+0x4c>

8038: ebfffff0 bl 8000 <foo>

803c: e1a03000 mov r3, r0

8040: e54b3005 strb r3, [fp, #-5]

8044: e59f002c ldr r0, [pc, #44] ; 8078 <_start+0x50>

8048: ebffffec bl 8000 <foo>

...

8074: 0000807c .word 0x0000807c

8078: 0000808c .word 0x0000808c

It places the absolute addresses to the two string literals at the end of the function and uses a PC-relative load instruction to fetch the values from the function trailer into register r0 before calling foo. A collection of such addresses at the end of a function is called a literal pool. For functions that access various different objects in the .data or .rodata sections, these pools can grow to a significant size. They need not only point to strings, the compiler also generates entries for other things like long program jumps, global variables or even C++ vtables.

Since these literal pools use absolute addresses, they can potentially disclose or narrow down the base address of the firmware blob. In the following section, I describe how this can be accomplished by identifying and linking pool addresses to string literals.

Algorithm Concept

For our scenario, we assume to have been given a binary firmware blob that runs on a 32bit ARM chip and operates on string literals, meaning that it accesses string constants in the .rodata section. We don’t know at which address the firmware is loaded into memory. This makes firmware analysis more complicated because code jumps, variables or strings that rely on absolute addressing cannot be resolved if the firmware is placed at an incorrect location. Hence, the goal of this algorithm is to determine the absolute address at which the firmware image is supposed to be loaded into memory.

Prerequisites

The algorithm has two prerequisites that must be extracted from the firmware image beforehand:

- The offsets to all string literals that can be identified in the firmware image

- The addresses contained in all identifyable literal pools

Although I list these steps as prerequisite, identifying the literal pool addresses can be considered an important step in the algorithm. The results of these two steps do not necessarily need to be perfect, i.e. can contain false positives, as long as the amount of identified literal pools and string constants is sufficiently high.

Algorithm Description

Since the compiler always creates literal pools for code that accesses string constants, we can assume that some of the literal pool addresses we identified in the last step must point to the string literals that we found. We can now try out different base addresses and determine the number of literal pool addresses that correctly link up with the identified string constants. The base address that maximizes this function can be considered the correct base address (given that we have correctly selected our candidate base addresses).

This algorithm turns our search into an optimization problem. The advantage of this is that we do not need to find all strings or all literal pools. As long as we find a sufficient number of samples, we can be sure that our algorithm will converge. However, it can also be considered somewhat of a brute-force method, and we need to be smart about what addresses we consider as possible load locations for the firmware. If we select an address range that is too broad, the algorithm will likely not terminate. Fortunately, the non-volatile memory of most embedded chips is rather small compared to the 32 bit address space. Additionally, we can assume the firmware addresses to be aligned to 0x4 or possibly even 0x10 boundaries to further narrow down the search space.

Algorithm Implementation

Given the theoretical description in the previous section, simply put, we need to do three things:

- Identify the string constants in the firmware image,

- Identify ARM literal pools in the firmeware image,

- Try out all possible base addresses to determine the one that maximizes the matches between literal pool addresses and string locations.

I implemented each step as part of a Python script. I published the full script as a GitHub Gist here. Below, I describe each step in greater detail.

String Search

I used the following function to find strings in the firmware. It does a simple regular expression search to determine string literals locations in the image.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

def find_string_positions(data: bytes, align: int = None) -> List[int]:

"""Find ASCII strings in the firmware blob and return the addresses

The function uses a regular expression to find the addresses of valid ASCII strings in the firmware.

If you set the align parameter to something other than None, make sure that the firmware blob is aligned to the

same value.

:param data: The firmware blob to search

:param align: If set to a value other than None, all returned addresses are aligned to this value.

:return: The addresses of valid strings in the firmware blob

"""

re_str = br'[\w\s\/*:,;$%&_-]{5,1000}'

regex = re.compile(re_str)

str_pos = [m.start() for m in regex.finditer(data)]

if align is not None:

str_pos = [p for p in str_pos if p % align == 0]

return str_pos

The function operates directly on the firmware blob and outputs all locations, i.e. offsets relative to the beginning of the file, that match the regular expression. The regular expression matches against all strings that consist of alphanumeric characters, spaces, and the list of special characters. This is not necessarily a very precise or exhaustive definition but appears to be sufficient for at least some cases. In order to avoid false positives, the function can optionally filter out all addresses that are not aligned on a four-byte boundary. Since the firmware runs on a 32bit ARM chip, we can assume all strings placed in the .rodata section by the compiler will have this alignment.

Literal Pool Search

The second step is to locate literal pools in the firmware image. This step is based on the publication mentioned above but uses a simpler heuristic to accept or reject literal pool candidates. The search operates directly on the binary file and does not require any prior analysis to detect code blocks.

The search assumes that a literal pool consists of multiple entries. All entries in such a pool must point to a certain region in address space. This is a valid assumption to make since we know the chip and its address mapping. If the firmware is loaded directly from the memory-mapped internal or external flash of the chip, the literal pools must point there. And since the size of most flash banks is rather limited, the valid address range is likely rather small. Consequently, we can assume a candidate pool to be valid if all addresses contained in it point to our target memory region.

The algorithm uses a dynamically-sized window that is moved across the entire firmware image. With every iteration, the algorithm checks if all values inside the window can be interpreted as absolute addresses pointing into a certain address range. If that is the case, the region is assumed to be a literal pool and the window size is increased until the check fails. All addresses are then added to a buffer, and the window is reset and moved to the next position. Below, I list the complete function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

def find_address_pools(data: bytes, target_range: Tuple[int, int], win_size: int = WIN_SIZE) -> List[int]:

"""Find ARM 32 bit address pools in the firmware and return the contained addresses

The function will only perform well if the target_range is narrow. Otherwise a lot of pools will be found.

Also, the firmware blob must be word-aligned.

:param data: The firmware blob to search for address pools

:param target_range: The target address range that the addresses must point to.

:param win_size: The minimum size that a pool must have

:return: A list of unique addresses that were found in the pools

"""

data_arr = np.frombuffer(data, dtype=np.uint32)

pos = 0

pool_size = win_size

candidates = set()

while (pos + pool_size) <= len(data_arr):

pool = data_arr[pos:pos + pool_size]

elements_in_range = np.logical_and(pool >= target_range[0], pool < target_range[1])

if not np.all(elements_in_range):

if pool_size > win_size:

# The last entry is not valid but we increased the pool size in the last iteration.

# That means that the last iteration contained a valid pool.

# Store the pool and reset the window

pos += pool_size - 1

candidates.update(pool[:-1])

else:

# Entries are not valid and we did not increase the window size in the last iteration

# Move the window

pos += 1

# Reset the pool size to default

pool_size = win_size

else:

# All items are valid, increase the pool size

pool_size += 1

return list(candidates)

The algorithm accepts the firmware image as binary blob, a target address range, and the minimum window size (which defaults to 3). The target address range parameter represents the range in address space that the values in a candidate literal pool must point to in order to be considered valid. In general, this will be the address range of the flash memory.

The algorithm first converts the binary firmware image into a numpy array of type uint32 with little endianess. Since all addresses inside a pool will be located on a 32 bit boundary, we can safely perform this conversion. The loop begins by placing the moving window at the beginning of the image. I then checks if all values inside the window are valid pool addresses, i.e. point into the target memory region. If that is the case, the window size is increased until the condition fails. All addresses in the pool are added to the result set and the window is reset to its minimum size and moved to the next position. This process is repeated until the window reaches the end of the image. The algorithm then returns a unique set of literal pool addresses as list.

Load Address Search

The last step is an exhaustive search over all possible firmware base addresses to determine the base address that maximizes the number of matches between literal pool addresses and string locations. Again, we must carefully consider the number of possible base addresses to not overwhelm the algorithm. If we select an address region that is too broad, the algorithm will not terminate. However, normally the range of valid base addresses is limited by the size of the ROM or RAM of the chip. Additionally, we can safely assume that the base address must at least align to a 4 byte boundary. Below, I show the code that performs the search.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

def count_matches_for_offsets(pool_addresses: np.ndarray,

str_offsets: np.ndarray,

candidate_load_addresses: List[int]) -> np.ndarray:

"""For each offset in the search range, count how many str_offsets match up with

the addr_pointers

This function correlates the offsets of the strings that were found in the firmware

to the target address pools. For each possible offset in offset_search_range, it

calculates how many of the pool_addresses match up with the

str_offsets + offset_search_range[i].

:param pool_addresses: The addresses that are supposed to point to the strings found

in the firmware

:param str_offsets: The offsets of all strings found in the firmware, relative to the

start of the file

:param candidate_load_addresses: The range of possible firmware offsets to try

:return: For each offset in fw_offset_range, the function returns the number of

pool_addresses that match up with the corresponding adjusted str_offsets.

"""

matches_lst = []

for i in tqdm(candidate_load_addresses, total=len(candidate_load_addresses)):

cur_target_offsets = str_offsets + i

intersect = np.intersect1d(pool_addresses, cur_target_offsets, assume_unique=True)

matches_lst.append([i, len(intersect)])

return np.array(matches_lst, dtype=np.uint64)

The function is given the list of literal pool addresses and string offsets determined previously. Both are provided as numpy arrays for easier handling. Third, the function requires the list of firmware base addresses for which to calculate the number of matches.

For every possible base address, the function calculates the intersection of literal pool addresses and absolute string offsets. The intersection is equivalent to the number of address pool entries that correctly match up with a string. The function returns an 2D array that list for each load offset the number matched strings.

Putting it all together

Lastly, I use the following code snippet with main function to put it all together. The window size is set to 3 and the word size is set to 4. The chip had an internal flash with an address range from 0x0 to 0x80000. Hence, I configured the target range to fall within that part of address space. Lastly, I set a step size of 0x10. This is an important hyperparameter, as it can lead to false results if set too big or cause the algorithm not to finish in time if set too small. In general, it shouldn’t need to be set to a value smaller than the word size of the system.

The main function itself chains together the functions explained above. It collects the string offsets and literal pool addresses. It converts the results into numpy arrays for easier handling. After calculating the match array, it determines the base address with the maximum number of matches and generates a plot for visualization.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

WIN_SIZE = 3

WORD_SIZE = 4

TARGET_RANGE = (0x0, 0x80000)

STEP_SIZE = 0x10

def main():

fpath = sys.argv[1]

with open(fpath, 'rb') as f:

firmware = f.read()

time_pre = time.time()

str_pos = find_string_positions(firmware, align=WORD_SIZE)

print(f"Found {len(str_pos)} unique strings")

pool_addresses = find_address_pools(firmware, target_range=TARGET_RANGE, win_size=WIN_SIZE)

print(f"Found {len(pool_addresses)} unique pool addresses")

str_pos_arr = np.array(str_pos)

pool_addresses_arr = np.array(pool_addresses)

search_range = range(TARGET_RANGE[0], TARGET_RANGE[1], STEP_SIZE)

matches = count_matches_for_offsets(pool_addresses_arr, str_pos_arr, list(search_range))

time_post = time.time()

runtime = time_post - time_pre

print(f"Total runtime: {runtime:.2f}s")

max_index = np.argmax(matches[:, 1])

max_offset, n_matches = matches[max_index]

print(f"Offset for max alignment: {max_offset:08x}")

print(f"Total matches: {n_matches}")

sns.set_theme()

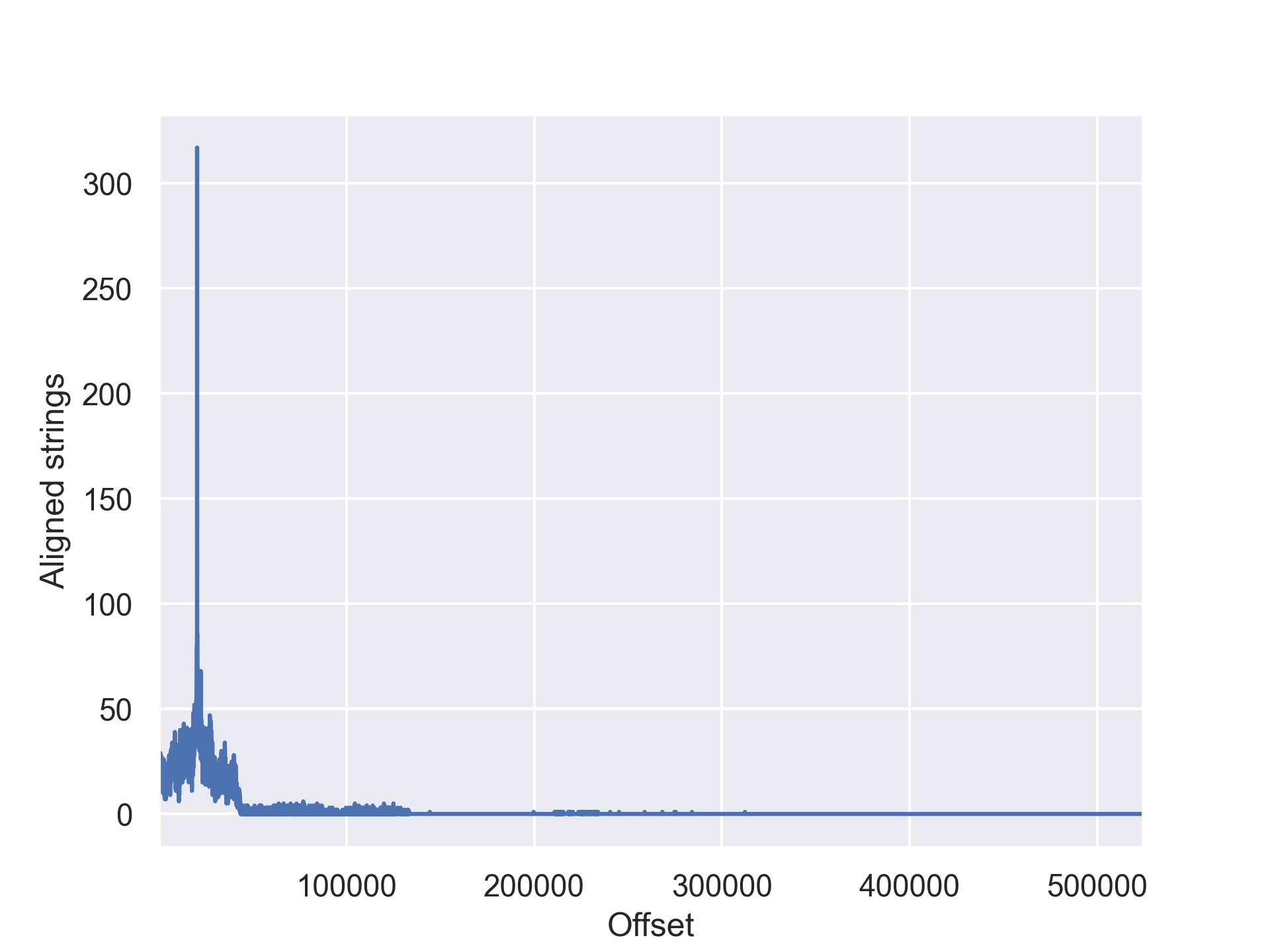

plt.plot(matches[:, 0], matches[:, 1])

plt.xlim(*TARGET_RANGE)

plt.xlabel('Offset')

plt.ylabel('Aligned strings')

plt.savefig('plot.png', dpi=300)

plt.show()

Base Address Discovery

When I ran the script with specified hyperparameters against my firmware blob, the code generated the following output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

Found 497 unique strings

Found 1455 unique pool addresses

100%|██████████| 32767/32767 [00:01<00:00, 18749.79it/s]

Total runtime: 2.26s

Offset for max alignment: 00004fe0

Total matches: 317

The search took a little over two seconds. The script found 497 unique strings and 1455 unique pool addresses. Using a base address of 0x4fe0, the script was able to match 317 of the strings to corresponding literal pool addresses. However, this information alone does not convey any information about the significance of the maximum that it determined. To give a visual impression of the significance, I show the generated graph below:

The figure shows a singular peak at offset 0x4fe0. The peak is very pronounced and represents a significant outlier in comparison to the remaining samples. Hence, it is safe to assume that this value represents the likely load address of the binary.

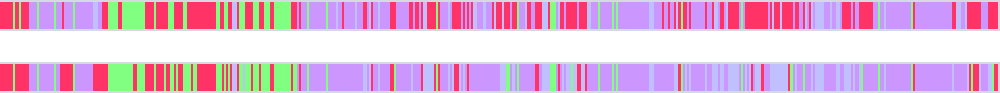

To give further weight to the result, I compared the auto analysis results of Ghidra for the default load address 0x0 and the result 0x4fe0. The figure below shows the (rotated) Overview sidebar in Ghidra for both analysis attempts. The width of the bar represents the length of the firmware image. The colors encode what data the analysis discovered in the firmware image. Purple indicates code, green indicates data, and red indicates unknown sections.

The figure shows quite nicely that the second iteration of the analysis with the discovered base address of 0x4fe0 lead to a significantly better result. Ghidra was able to discover more instructions across the entire firmware image and more accurately link references to the data section of the image.

Given the collective results above, 0x4fe0 appears to be the correct base address for the firmware image.

Hyperparameter Tuning

Lastly, I wanted to check how the selection of the step size would affect the accuracy of the result. Below, I list the result for multiple iterations with varyiing step sizes:

| Step Size | Runtime | Matches | Base Address |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0x1 | 28.80s | 317 | 0x4fe0 |

| 0x4 | 7.47s | 317 | 0x4fe0 |

| 0x10 | 2.26s | 317 | 0x4fe0 |

| 0x40 | 1.48s | 89 | 0x5000 |

| 0x2000 | 0.70s | 36 | 0x4000 |

In our case, decreasing the steps size did not yield any improvement, further demonstrating the correctness of the result. However, increasing the step size past a value of 0x10 caused the algorithm to miss the absolute maximum. Nevertheless, the determined maximum remained as close to the actual maximum as possible. This would indicate that it is possible to safe computation time in large searches by iteratively decreasing the target address range along with the step size.

Conclusion

By using the method proposed in the paper by Zhu et al., I was able to correctly determine the base address of the firmware image I was dealing with. Furthermore, I hope that the code I posted here (and in the GitHub Gist) can be of use to someone else.